If you’re asking yourself how to make an artificial manager, there’s probably a difficulty that comes to mind, which prevents us from programming managerial actions according to some pattern or predetermined procedure. This difficulty is the fact that in the management of a company, project or team, there is no such pattern or one course of action that always works. Every business situation is different, and even every day spent with his team brings different challenges to the manager that he has not encountered before.

Therefore, a manager must constantly adjust his actions, take into account new circumstances and build on past experience. In other words – he must prototype.

The organizational size system together with online managerial tools are great for recording these changes in managerial behavior and then correcting the manager’s robotic actions.

In 2020, as part of The European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, which I have been attending for more than 10 years, I published a paper showing the phenomenon of managers prototyping their actions as recorded by online managerial tools on the TransistorsHead.com platform.

As part of my research projects on team management in 2019, I organized a long-term observation of students who were planning their business projects. The study investigated the trajectory of managerial actions taken by managers among students of Human Resource Management at the Faculty of Psychology at the University of Silesia in Katowice. They were tasked with carrying out a given project from idea to final presentation, which concerned organizational solutions at one of Poland’s universities aimed at development in the academic achievements of academic staff. The problem to be solved by the students: a major Polish university planned to be a research university from 2020.

Participants in the study worked in teams of 4-5 people. Both the manager and team members used online management tools at Transistorshead.com. The tools recorded the participants’ behavior, which made it possible to find out what types of managerial actions they took, in what order, and what the characteristics of those actions were.

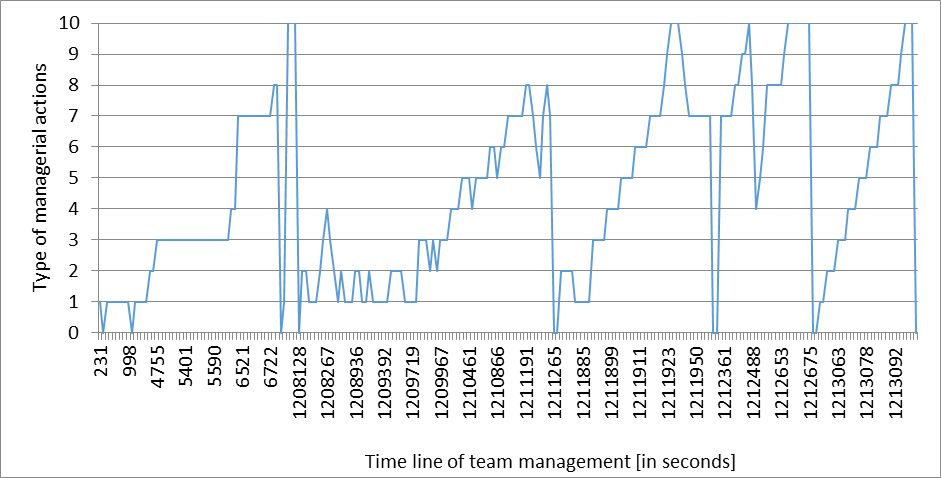

An example of a recorded team management trajectory by one of the managers participating in the study is shown in Figure 1. This manager took 232 managerial actions, started at 10:58 a.m. on May 14, 2019, and finished at 11:56 a.m. on May 28, 2019, and his actual team work lasted 1213107 seconds. As can be seen in Figure 1, the trajectory of team management began with setting goals (managerial activity 1) repeated twice, then the manager moved on to describing tasks (managerial activity 2), and then to generating ideas (managerial activity 3), and so on.

Figure 1. Trajectory of managerial activities

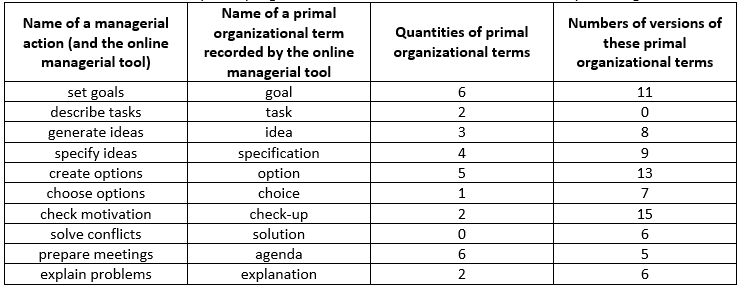

I show the numbers of created primary organizational terms and their versions (edited and revised) in Figure 2. It can be read from it that this manager created 6 goals, but in 11 versions, 5 decision options in 13 versions, etc. Since each object (primary organizational size) can only be in one version at a given moment in time, this means that these 6 goals were changed several times (there were 11 changes).

Figure 2. the number of primary organizational terms and the number of their versions

The change of once established primary organizational terms can be seen, moreover, in Figure 1 – the manager repeatedly returned to the same tool and edited objects. This gives an idea of how much a person changes once made arrangements and reacts to the circumstances in which he finds himself. This affects the performance of the artificial manager – he must react similarly, be flexible in his actions and correct issues once established.

Read more: